Abstract

Takayasu Arteritis (TA), a rare large-vessel vasculitis, presents significant diagnostic and management challenges, particularly in resource-limited settings such as São Tomé and Príncipe, a small island nation in Central Africa. This article explores the complexities of diagnosing and treating TA in this context, highlighting systemic healthcare constraints, limited access to diagnostic tools, and cultural barriers. Through a situational analysis of São Tomé and Príncipe’s healthcare landscape and a comprehensive literature review, the paper identifies gaps in awareness, expertise, and infrastructure that hinder effective care for TA patients. The etiology of TA, including potential autoimmune mechanisms and speculative links to vaccinations, is also discussed. Recommendations are provided to improve diagnosis and management, emphasizing capacity building, international collaboration, and public health initiatives. This paper underscores the need for tailored approaches to address rare diseases in under-resourced regions, offering insights that may be applicable to similar contexts globally.

Introduction

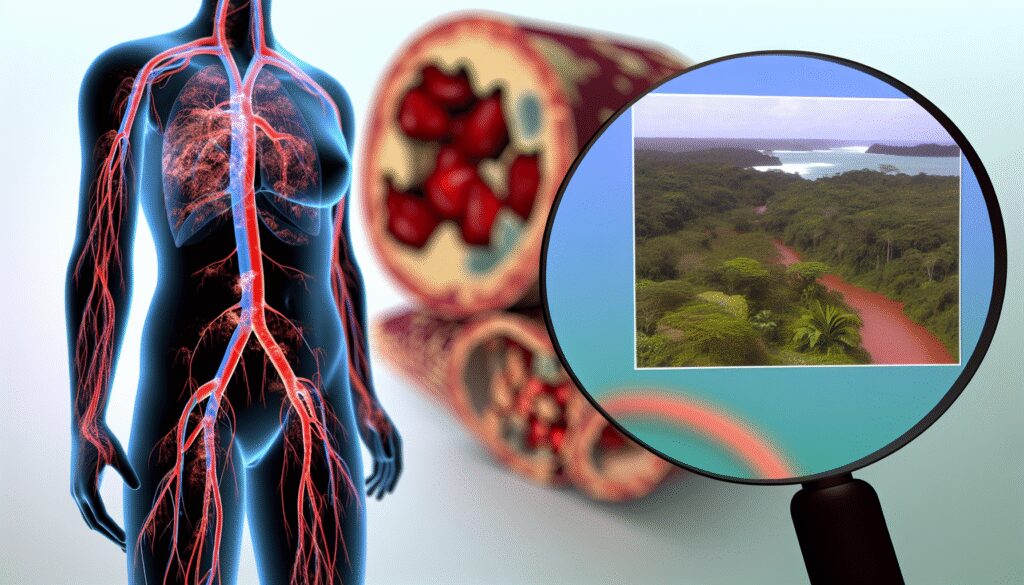

Takayasu Arteritis (TA), also known as “pulseless disease,” is a chronic inflammatory condition that predominantly affects large blood vessels, such as the aorta and its major branches. Primarily impacting young females, TA leads to vascular stenosis, occlusion, and, in some cases, aneurysms, resulting in severe complications such as stroke, heart failure, and limb ischemia. The global incidence of TA varies, with higher prevalence reported in Asian populations, though data from African regions remain sparse due to underdiagnosis and limited reporting.

In São Tomé and Príncipe, a small island nation with a population of approximately 220,000, the healthcare system faces significant challenges, including limited access to specialized care, diagnostic imaging, and rheumatologic expertise. These systemic barriers exacerbate the difficulties in diagnosing and managing rare diseases like TA. This article aims to provide a detailed examination of the challenges specific to São Tomé and Príncipe, contextualized within broader global perspectives on TA. By integrating local realities with existing literature, this paper seeks to highlight actionable strategies to improve outcomes for TA patients in such settings.

The paper is structured to first present a situational analysis of São Tomé and Príncipe’s healthcare environment, followed by a literature review of TA’s clinical features, etiology, and management. A discussion on the intersection of local challenges and disease characteristics ensues, with a focus on potential autoimmune links and speculative vaccine associations. Finally, recommendations and conclusions are offered to guide future interventions.

Situational Analysis: Healthcare in São Tomé and Príncipe

São Tomé and Príncipe, located in the Gulf of Guinea, is one of Africa’s smallest countries, comprising two main islands and several smaller islets. Despite being classified as a lower-middle-income country by the World Bank, the nation grapples with significant socioeconomic and health challenges. The healthcare system is characterized by a limited number of facilities, with the central hospital, Hospital Dr. Ayres de Menezes, serving as the primary referral center. However, this facility often lacks the equipment and personnel necessary for diagnosing and managing complex conditions like TA.

Primary healthcare is delivered through small health centers across the islands, but these are frequently understaffed and under-equipped. Access to specialists, such as rheumatologists or vascular surgeons, is virtually nonexistent locally, necessitating costly referrals to Portugal or other countries for those who can afford it. Diagnostic capabilities are further constrained by the absence of advanced imaging modalities like magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or computed tomography angiography (CTA), which are critical for confirming TA diagnoses.

Cultural factors also play a role in delaying diagnosis and treatment. Many patients initially seek care from traditional healers, attributing symptoms such as fatigue, fever, or limb pain to spiritual causes rather than medical conditions. This delays presentation to formal healthcare facilities, often until TA has progressed to advanced stages with irreversible vascular damage.

Moreover, there is a general lack of awareness about rare diseases among both healthcare providers and the public in São Tomé and Príncipe. Training for medical professionals is limited, and continuing medical education opportunities are scarce. Without specific knowledge of TA’s clinical manifestations—such as absent pulses, claudication, or systemic symptoms—misdiagnosis as more common conditions like hypertension or tuberculosis is frequent, further complicating patient outcomes.

Literature Review

TA is a rare idiopathic vasculitis with an estimated incidence of 1 to 2 cases per million per year in Western countries, though it may be higher in regions like Asia and possibly Africa, where data are limited (JACC, 2023). The disease typically presents in two phases: an early “prepulseless” phase characterized by nonspecific constitutional symptoms (e.g., fever, fatigue, weight loss) and a later chronic phase marked by vascular occlusion and ischemic symptoms (UpToDate, 2023). This biphasic presentation often leads to missed diagnoses in the early stage, especially in settings with limited diagnostic resources.

Etiology and Autoimmune Links: The exact etiology of TA remains unknown, though it is widely accepted to involve an autoimmune mechanism. Genetic predispositions, particularly associations with the HLA-B*52 allele, have been identified in certain populations, suggesting a hereditary component (The Rheumatologist, 2025). Immune dysregulation, characterized by T-cell infiltration and granulomatous inflammation of the vessel walls, is a hallmark of TA. Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) further support the autoimmune hypothesis (Frontiers, 2025). Environmental triggers, including infections, have been proposed as potential initiators of this aberrant immune response, though no specific pathogen has been consistently implicated.

Speculative Links to Vaccines: The potential link between TA and vaccinations, particularly the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, has been explored in historical literature. Some studies have hypothesized that BCG, which is widely administered in tuberculosis-endemic regions, may act as an immunological trigger for TA in genetically susceptible individuals due to cross-reactivity with vascular antigens (ScienceDirect, 2004). However, this association remains speculative and lacks robust epidemiological evidence. Given the widespread use of BCG and the rarity of TA, any causal relationship is difficult to establish, and current consensus does not support avoiding routine vaccinations based on this theory. In São Tomé and Príncipe, where BCG vaccination is part of the national immunization program, no specific data link TA incidence to vaccine exposure, though further research is warranted in diverse populations.

Diagnosis and Management: Diagnosis of TA relies on clinical suspicion, supported by imaging and laboratory findings. Criteria established by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) emphasize features such as age at onset (under 40 years), claudication, and angiographic abnormalities (Mayo Clinic, 2023). However, in resource-limited settings, access to angiography or even basic ultrasonography is often unattainable, leading to reliance on clinical judgment alone.

Management of TA involves a combination of immunosuppressive therapy (e.g., corticosteroids, methotrexate, or biologics like tocilizumab) to control inflammation and surgical interventions for severe vascular complications (Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 2021). Monitoring disease activity through inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is standard but may be hampered by inconsistent laboratory access in regions like São Tomé and Príncipe. Long-term follow-up is critical due to the risk of relapse and complications such as cardiovascular events, yet continuity of care remains a challenge in under-resourced systems.

Discussion

The challenges of diagnosing and managing TA in São Tomé and Príncipe are emblematic of broader issues faced by low-resource settings in addressing rare diseases. The early, nonspecific symptoms of TA align poorly with the diagnostic capacities available locally. For instance, the absence of MRA or CTA means that clinicians must rely on physical findings like pulse discrepancies or bruits, which may not manifest until late in the disease course. This delay in diagnosis often results in irreversible vascular damage, significantly worsening prognosis.

Management is equally problematic. Corticosteroids, the cornerstone of TA treatment, are not always available in sufficient quantities, and their long-term use raises concerns about side effects such as diabetes and osteoporosis, which are difficult to monitor without adequate laboratory support. Access to biologics, which have shown promise in refractory cases, is beyond the reach of most patients due to cost and supply chain issues. Surgical options for managing stenotic or aneurysmal lesions are similarly limited, as vascular surgery expertise is not locally available, and referrals abroad are prohibitively expensive for the majority of the population.

Cultural perceptions of illness further complicate care. Many individuals in São Tomé and Príncipe first consult traditional healers, delaying medical intervention. This is compounded by low health literacy, which hinders recognition of alarming symptoms and adherence to complex treatment regimens. Community-based education could play a pivotal role in addressing these barriers, but such initiatives are currently underdeveloped.

Regarding etiology, the autoimmune nature of TA suggests that environmental and genetic factors likely interact to precipitate disease onset. In São Tomé and Príncipe, where infectious diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis are prevalent, it is plausible that infections could act as triggers for immune dysregulation in susceptible individuals. The speculative link to BCG vaccination, while intriguing, lacks sufficient evidence to influence clinical practice. Given the importance of vaccination programs in controlling infectious diseases in the region, any theoretical risk associated with BCG must be weighed against its proven benefits. Future studies, ideally involving international collaboration to pool data from African cohorts, could clarify whether vaccine-related immune responses contribute to TA in specific populations.

Additionally, the burden of cardiovascular risk factors, which exacerbate TA-related complications, must be addressed. Studies indicate that hypertension and dyslipidemia are common among TA patients globally (Rheumatology, 2017). In São Tomé and Príncipe, where non-communicable diseases are rising, integrating cardiovascular risk management into TA care is essential but challenging due to resource constraints.

Recommendations

To improve the diagnosis and management of TA in São Tomé and Príncipe, a multi-faceted approach is necessary, encompassing capacity building, infrastructure development, and community engagement. The following recommendations are proposed:

- Training and Education for Healthcare Providers: Implement targeted training programs for general practitioners and nurses to recognize early symptoms of TA and understand referral pathways. Partnerships with international medical organizations or universities could facilitate workshops or telemedicine-based mentorship programs to build local expertise.

- Enhancement of Diagnostic Capabilities: Invest in portable ultrasonography equipment, which is more feasible than MRA or CTA for resource-limited settings, to aid in early detection of vascular abnormalities. International aid or grants could support the acquisition of such technology, alongside training in its use.

- Access to Medications: Establish a reliable supply chain for essential medications like corticosteroids and immunosuppressants through partnerships with pharmaceutical companies or global health initiatives. Generic formulations could reduce costs without compromising efficacy.

- Community Awareness Campaigns: Develop culturally sensitive education programs to increase awareness of TA symptoms and the importance of seeking timely medical care. Collaboration with community leaders and traditional healers could enhance the impact of these initiatives.

- Research and Data Collection: Encourage local data collection on TA incidence and outcomes to inform policy and resource allocation. Participation in international registries or research networks could provide insights into region-specific disease patterns and risk factors, including potential vaccine associations.

- Policy Advocacy: Advocate for the inclusion of rare disease management in national health policies, ensuring that conditions like TA receive attention despite their low prevalence. This could involve creating referral systems for overseas treatment subsidized by the government or international partners for cases requiring advanced interventions.

These strategies, while tailored to São Tomé and Príncipe, may also apply to other small island nations or low-income settings facing similar challenges with rare diseases. Implementation will require sustained commitment from local authorities, alongside support from global health stakeholders.

Conclusion

Takayasu Arteritis poses significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in São Tomé and Príncipe, reflecting the broader difficulties of managing rare diseases in resource-limited environments. The interplay of limited healthcare infrastructure, cultural barriers, and lack of awareness contributes to delayed diagnoses and suboptimal outcomes for affected individuals. While the etiology of TA remains incompletely understood, its likely autoimmune basis and the speculative link to vaccines highlight the need for further research, particularly in understudied African populations. Through targeted interventions—ranging from provider training and diagnostic enhancements to community education and policy advocacy—it is possible to mitigate some of these challenges and improve care for TA patients. This article serves as a call to action for local and international stakeholders to prioritize rare disease management in resource-constrained settings, ensuring equitable health outcomes for all.

References

- JACC. (2023). Takayasu Arteritis: JACC Focus Seminar 3/4. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. Available at: https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.09.051

- Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. (2021). French recommendations for the management of Takayasu’s arteritis. Available at: https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-021-01922-1

- ScienceDirect. (2004). Aetiopathogenesis of Takayasu’s arteritis and BCG vaccination: The missing link? Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0306987795901094

- UpToDate. (2023). Clinical features and diagnosis of Takayasu arteritis. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-features-and-diagnosis-of-takayasu-arteritis

- Mayo Clinic. (2023). Takayasu’s arteritis – Symptoms & causes. Available at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/takayasus-arteritis/symptoms-causes/syc-20351335

- Rheumatology (Oxford Academic). (2017). Assessment of the frequency of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/rheumatology/article/56/11/1939/4079919

- The Rheumatologist. (2025). New Analysis Reveals More Potential Contributors to Takayasu Arteritis. Available at: https://the-rheumatologist.org/article/new-analysis-reveals-more-potential-contributors-to-takayasu-arteritis

- Frontiers. (2025). Hyperhomocysteinemia in Takayasu arteritis—genetically defined or burden of the proinflammatory state? Available at: https://frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1574479/full